“Let each note be, a full-bodied song.” - Lyric, “En Gallop!” by musician Joanna Newsom (in her early, non-studio EP ‘Walnut Whales’)

There are four different types of kind of filmmaker that could be attributive of Tobe Hooper, receivable to the public gaze. But, unlike the esteemed hustler-artists of Hollywood walking the tightrope of their inner charity (their cinema “Good Work”) and their outer chutzpah, for instance (and however that may manifest), it is quite different with Hooper in that there is no great need to separate the constitutive types that conceivably make him up. For unlike Scorsese and his film-loving saintliness put up against his latest immediately-appealing ode to the glamorous, if self-sacrificial, narcissist, or Spielberg and his “Serious Picture”/“Entertainment Picture” alternation (but is there ever really a difference?), Hooper is a presence totally reconcilable, between the various masks he puts on as a filmmaker, between his modest compact with the medium of film and the films he boldly puts forth in the offering, found in the purity and the venerability of his works.

Hooper is first and foremost known as the creator of that horror cinema sacred cow The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974). No one dare besmirch it, even those who find its grindhouse flavor a reason to pinpoint Hooper as a reductive filmmaker, lacking the range, imagination, and imaginative transcendence to ever be a popular filmmaker. Hooper is the failed blockbuster filmmaker, whose post-Poltergeist bid to be such – to capture the imagination of movie fantasy-seekers on a level of mass genre spectacle – proved unfruitful.

Thirdly, Hooper is a nonconformist “experimenter,” whose failure to become a studio staple (despite such a situation being the most desirable and inspiring position for him, so say I and so probably would he say, both to our chagrin) can be chalked up to his more outré proclivities and preoccupations. His perceived perversity and uninvolved – or unevolving – instincts were more empty ammunition for those previously mentioned persons not buying what Hooper was selling, perceiving Hooper as the most regressive of cultural creators, always returning to the slop trough of the grim, the lurid, and the “childish” effects seen at their root in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (and his excellent but probably ill-chosen follow-up Eaten Alive, a direct expansion on the same artistic enterprise he pursued with Texas Chain Saw Massacre, but very much not a strategic move to show off his range).

But what is scatological to some is a transcendence to others, and I do not mean in the “cultural critic” sense of touting the low culture, of finding sympathy and sensibility in the “bad” or depraved. Hooper, rather, inhabits a realm of classical ideals of art that imbue everything he does with the venerable desire to be “Good” belonging to the utmost Rational artist – meaning, in a sense of moral-aesthetic purposes that are opposed to depravity unmediated, to the negative valuing of aesthetic ideals (as opposed to short-term, empirical, sensuous measures), to crassness resulted from a void of philosophy. It is s/he – the perfect Rational artist – who pursues first and foremost the perfect aesthetic Idea before the catering to audience expectations and the simplicities of thoroughgoing narrative telling. Hooper’s willingness to approach “low genre” with respect shows instead a sacrifice, a transcendence, made according to a genre-blind and teleological point of view towards this visual-narrative form that has always been doused in moral-aesthetic contradictions, but can actually dovetail totally and completely into the Good, in spite of and because of art not in a vacuum but ineluctably part of a difficult, contradictory world. What to make, then, of Hooper’s clear placement in Hollywood’s capitalist market history? Just this. It is the sense of venerable artistic regeneration in a contradictory system of art and commerce. His nostalgia for the old studio system (responsible for so many classicalist works, early as it was in cinema history when film was still traditionally seen, for the most part, as an outgrowth of the preindustrial, classical forms of art) and his induction into the industry’s newest neoliberal-era incarnation resulted in a struggle and a crash, and, indeed, some of the most transcendently contradictory works to come out of the trends of his time.

Hooper’s undoubted fondness for the horror genre relates back to an interest in eternal – or “Absolute,” in philosophic terms – existential realities such as death and moral defeat, if not directly to its worldlier aspects of sex, psychology, and violence. That his chosen genre indulges in such negative and fetishistic cultural vogues is only the gambit that he is willing to make, in order to see for himself the juxtaposition of a moral and philosophical art-making with the thornier aspect of our cultural intake, which, so he sees, is actually ennobled by the unflinching, subconscious “throw-up” – Hooper’s phraseology – of social and existential anxieties that is the horror genre. Throughout all his films (save for two ventures into unfettered “genre melodrama” in 1990 and 1995), he displays only an acumen for the analysis of such cultural baggage that comes with his symbolic filmmaking, a seriousness of purpose that not only trades in Hooper’s penchant for narrative metaphor beneath genre surfaces, but deigns itself to redeem an infantile genre with neoclassicist ideals (as outmoded as those can be in an empirical and postmodern age, Hooper nevertheless believes in a Platonic art). Thus is realized the transcendence of all things perceived debased through the excellence of a philosophical work. The career goals may remain unrealized, but the moral teleology remains: Platonic ideals – like the Form of Goodness, contained in cinema – found within perceived hang-ups, within genres that mostly serve to please immediately through the dissolute senses yet can, at its best, edify and offer Knowledge indefinitely through a pure, aesthetical reason. The ideal Forms of Plato hold no physical existence – they hover above the material embodiments and the simpler, shallower results of that which is perceived, and so does Hooper work towards a filmmaking of Form, where the commercially-based designation that is genre, as well as manipulations and commercial designs in general, exerts no constrictions on Hooper’s hovering, unconsciously neoclassical work, which reject the material embodiments of conventional entertainment and reach for further Truths. This is, of course, not how all filmmaking of grand, moral gestures work, but this is how Hooper works.

But let us return to listing the conventional perceptions of Hooper: fourthly, he is seen as and venerated as a Master of Horror, worshipped for his dark imagination, expected to be black-garbed and profane-minded, sick but sensitive, a lover of the beauteously horrific and a Gothic artist in the great tradition of Stoker, Shelley, Lovecraft and Poe in the literary annals, those cultish figures of touted, culturally lofted pulp; deeply revealing and deeply aesthetical pulp, but still pulp. The truth is that many of our most worshipped horror filmmakers are simply stuck, would wish and have the desire to make any sort of film they want, but regrettably are caught in the vise of a business model where films cost prohibitively much and are too much of a cultural product to allow anyone to do whatever they want, that is, without the risk of getting unstuck from the system completely. They need the approval of both the moneyed producers and the culture itself, of which producers can be said to be its representatives. In any case, Hooper would always lean toward darkness to provide for the masses – after all, his is the mind that came up with The Texas Chain Saw Massacre.

But the desire to psychoanalyze Hooper and his morbid fascinations is again something that must be deprioritized, for it first marginalizes Hooper as a creator of “horror things” (more often than not a juvenile designation), and secondly, it is directly contradicted by the artistic aspect for which he should be praised which is the remarkable neutrality of his cinema. This is a multifaceted aspect that must be broken apart delicately. Many auteurfilmmakers trade in the revealing of their deepest selves – intentionally or unintentionally – within their films, whether psychological hang-ups or their self-image as individuals or as artists. Hooper’s work hangs before us rather unmatched as a display of artistic creation removed from “the self,” varied and expressly universal in its moral and aesthetic concerns, reaching far past the more low-hanging cinematic fruit that broker in an artist’s messy psychological purging (or, lower-hanging yet, involving artists’ bids for career prestige, resulting in increasingly bombastic and narcissistic works of great navel-gazing). Best-case scenario of this is Fassbinder’s highly explorative personal film exorcisms (while the best worst-case scenario is Turkish auteur Nuri Bilge Ceylan treating artfully his strange, romantic ideals of modern sexism). Hooper’s work seems to – to as minimal an extent as it would seem possible for an artist – insist on no matters of himself, so far as his subject matter pertains not specifically to himself but to the world at large (of which he is a part of). Neither does he feel compelled to create a “signature style” or popular visual “sensibility,” tied to a self-image of him as an artist-of-sensibility. Neither can the diversity, or the pronounced androgyny, of his catalogue of work be denied. More often than not, Hooper designates female characters to be his wise surrogates with which to neutrally view the world, thus giving attention, as well as credence, over to lives from which he is so very far removed. With no disrespect to either of these masters of the cinema, it can be said that there is something a little obscene about John Ford's heroic tales of Manifest Destiny and male self-loathing (spiced up with romantic silhouettes), or John Carpenter's apocalypse fantasies, tied with lean and violent frames of comic book expressiveness (while Laurie Strode is a heroine objectified rather than related to). Hooper’s auteuristedges, contrary to what The Texas Chain Saw Massacre suggests, seem thoroughly softened, permeable to feminine wisdom, soon going so far as to sublimate his grim morbidity in order to adapt Spielbergian optimism to a more esoteric realm of beauty and dread in Poltergeist (1982), or to extol non-narcissistic love and a possible bright future in Lifeforce (1985) and Spontaneous Combustion (1990).

Thus, it is important to see Hooper as ever adaptable. He himself has stated his own personal objective to never carry over the same aesthetic goals from one film to another (although he surely does so), to learn with each new picture, to “change with the world,” in relation to his creation of work. In this statement again we see the lack of personal self-creation, the absence of self-image, as any ideas of self are automatically subjugated to principles of educative art and aesthetics that he holds, which is no less tied with a wish to respond to the world and its contemporary realities – and not just simply his place in it (an impulse easily identifiable in flash-in-the-pan “topical” films out of Hollywood), but with a totalizing existential vision (see Texas Chain Saw as his premiere exhibition of this). Hooper prostrates himself to the dictates of a totalizing art, the possible moral communications, and the contents of the world itself. In the diversity of his works, he, as a personality, is evaporated – sublimated, one could say – into the Forms of aesthetic and moral ideals.

Sublimation, in the psychological sense, is – as it is most basically known and described by Freudian schools – the channeling of baser impulses into behavior and practices of the higher, more moral faculties. Meanwhile, the more relativist, post-Enlightenment Nietzsche said of sublimation that it does not demarcate the moral versus the immoral, but blurs the boundaries between what is constructive and destructive to the social fabric, which is not at all causally related to morality or immorality, altruism or self-interest. From Human, All Too Human by Nietzsche, he wrote:

“There is, strictly speaking, neither unselfish conduct, nor a wholly disinterested point of view. Both are simply sublimations in which the basic element seems almost evaporated and betrays its presence only to the keenest observation… But what if… even in its domain, the most magnificent results were attained with the basest and most despised ingredients?… Mankind loves to put by the questions of its origin and beginning: must one not be almost inhuman in order to follow the opposite course?”

Hooper embodies both these conceptions through his idealism and, alternately, the distance, ambivalence, and resignation he takes on towards the idea of the world as ideal, as a religiously procured “safe bet” of Manichaean duality. The real world – that which Hooper treats with such respect in his films – is in fact not, yet this is the underlying principle beneath the capitalist, populist Christian market, infused with emotionally placatory genre work. Hooper utilizes a peripheral penchant for the “inhuman” viewpoint, as seen in his more unforgiving and unpalatable work, in order to achieve the capacity for analysis. The greatest empiricist artists often have to be the hardest and least sentimental artists: Kubrick certainly worked as such, and his works only barely seem to cross over into the realm of the moral (Nietzsche would have championed him – Also Sprach Zarathustra, after all, Kubrick the Zoroastrian Übermensch looking brazenly down at a world seen as empirically past the point of moral convention; 2001’s space child seems almost an idealist outlier in this regard to philosophical nihilism, ironically influencing Hooper’s comparable solitary venture into science fiction and metaphysics with Lifeforce). Hooper also often deems it necessary to separate himself from the valley of the “tasteful” and the “socially accepted” – in order to fully see the world and its course – but sublimates himself even further, past his and Kubrick’s grim realism and back again to Plato’s Forms (Absolutes, such as the Good, existing beyond the empirical), where even Kubrick’s grandiose, bordering-religious designs fade and Hooper’s permeable search for aesthetic ideals in the “natural,” “changing” world begin again (Kant informs Hooper, not Nietzsche). Again, here, we have Hooper existing as the perfect reconciliatory artist – between art and morality, Truth as an invention and the real – in a world of contradictions and subliminal self-involvements.

The “basic element” for Hooper-as-sublimated-artist is found in him not being a purveyor of culture, but a participant – an observer placed alongside his characters and not an overseeing God of narrative. He reacts as much as he creates (and create he does, but unlike many filmmakers who deem only to create, with wanton abandon). This reaches farther back than The Texas Chain Saw Massacre and finds its root in his previous work in the field of documentary. In these works, he does not create the content (nor overly manipulate it) for he does not create the world. Yet, the same sense of imagery and visual style we see from Texas Chain Saw and on already manifests itself. More explicitly than when he is on his constructed studio sets or with his malleable actors, Hooper is seen taking the materials already existing around him and executes his cinema – with the same sense of eagerness – using only that. This principle and zeal is simply carried on to his fiction films, the sets that are built for him or the locations he is given playing very integrally and importantly in his mise en scène. Hooper’s attention to the real material of architecture, landscape, décor, and the delicate moves of the camera inspired by therein, makes him the equivalent of a Vincente Minnelli within his darker, grittier genre.

As with the great aesthetician Minnelli (who himself fights off belittling labels of being “simply” a metteur en scène due to his work in abject genre, the Hollywood musical or melodrama), it is not just content and not just aesthetics, but a reconciliation of the two into a single Ideal: an aesthetical content, a plastic and non-manipulating thing, in which the most he can do is promote both the viewer’s propriety (Knowledge, reason) and their emotion (Beauty, the aesthetical cinema), combined, in order to provide an art not of-the-self, but of-the-world. Cannot these metteurs en scène then be seen as equal to the auteur, for their more purely humanist work? For Hooper (and I would also argue Minnelli) does not partake in content to promote transference of viewer into remote heroic fantasies, in which the world and the audience is idealized by way of sheer narrative escape. He does not partake in a conventional cinema, but in a differently beautiful sort that does not separate Beauty from the application of hardest, reflective knowledge: a mournful cinema. This cinema does not partake in the pleasures of cinema without the accompanying cries (the consequence of beauty, the netherworld stock, for only Death finally stifles the cries; many a Minnelli film also trades in matters of death, as well). In Hooper’s oeuvre, the cries reveal themselves as balefulness for political quiet (Eggshells), for social balance (Texas Chain Saw, Eaten Alive, Salem’s Lot), for peace in our human phases of growth (The Funhouse, Lifeforce), for a stable future divorced from a compromised past (Spontaneous Combustion), or for some wisdom in our socially embedded systems (Night Terrors, The Mangler).

1. Hooper, the Heavenly Sent

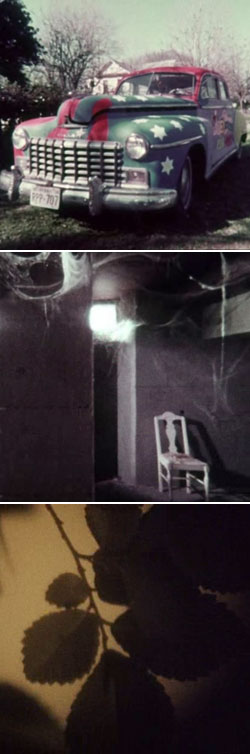

Before The Texas Chain Saw Massacre came Eggshells (1969). It may be a more accurate forebear to the unified filmmaker that would emerge. Eggshells is an experimental feature displaying a hybridized method of shooting, depicting cinéma vérité-style the mundane goings-on of the real-life inhabitants of an Austin, Texas communal house – consisting of a group of young, twenty-something hippie renters (and real-life acquaintances of Hooper) – while crafting a faint end-of-an-era narrative by sprinkling staged and re-staged scenes of the group, consisting of two couples, one real, the other fictionalized, in mostly-improvised dialogues. Inspired by a diet of experimental film at the time, Hooper utilizes only a skeletal narrative arc to act as jumping-off point for a series of abstract filmic digressions into experimental techniques (such as flicker editing, stop-motion, even one instance of pure animation), while fictionalizing a fantasy subplot concerning a supernatural “energy” taking roost in the house basement, allowing for a number of surrealist set-pieces based in a realm of abstract metaphor. It is a most literal example of Hooper deigning to draw cinematic and poetic inspiration from the world already existing, centering completely on matters of contemporary social relevancy and a pre-given house that he renders to its utmost visual potential. Walls are the preexisting material with which he creates his cinema and a metaphorical narrative: an enclosure for dramatized allegory, a fortress that soundly serves only to reflect the wider world that lies at its permeable barrier. The social relevancy would be carried over into Texas Chain Saw Massacre. The prominence and dilemma of domestic and other walls (and the occasional windows) would recur in Texas Chain Saw, Eaten Alive (1977), Poltergeist, Lifeforce, Night Terrors (1993), and Toolbox Murders (2005).

Prior even to Eggshells – which was inspired by avant-garde artists and documentarians – Hooper proved himself a filmmaker of a limitless, non-individualistic host of inspirations, as well as allegorical proclivities. At the end of his college years studying film at the University of Austin, he would mount a Medieval-set narrative short subject that showed off an inestimable amount of stylistic confidence and metaphorical interest, wholly concerned as it is with representing allegorically the corrupt characteristics of the sapient world. A Gothic costume piece crossed with old Warner Brothers cartoons (adapting to live-action their self-reflexive slapstick), it was a ten-minute modernist parody titled The Heisters (1964). It depicted a trio of olden thieves who take shelter with their loot in an underground hideout, only for the situation to end in their shared annihilation due to each their epitomizing of ever-modern symptoms of civilization: greed, bellicosity, and scientific inhumanity. Concurrently, he pays homage to Chuck Jones and Roger Corman, but to so pure and reverential an extent there is no sense of cannibalizing them – utilizing others’ styles in order to make something self-tailored and his own. The reflexivity is thus wholly sincere rather than postmodern (a trait suggesting personal rebellion uncharacteristic of Hooper), making it simply apiece with modernist trends rather than a simple send-up (the absurdist costumed role-playing is itself a trope of modernist arts, later to be seen within the film medium in the mimes of Antonioni’s Blow-Up, while the piece’s concentrated existentialist conceit speaks for itself).

Not quite clear whether finished before or after Eggshells, Hooper would complete his CV of notable pre-Chain Saw work with an hour-long cinéma vérité documentary that followed a touring stint of the popular activist folk group Peter, Paul, and Mary, titled Peter, Paul, and Mary: Song is Love (shot in 1969 and picked up by the PBS network for televising in 1970). Although mainly a commission job by an Austin producer, it is an absolutely political work by Hooper, striking, passionate, and posed to resurface (as it is essentially unavailable on home media, outside of those prescient enough to have taped it during its decade of rebroadcast), suggesting D.A. Pennebaker with a musical sense and Kubrickian aspirations.

2. Hooper, the Moral Author

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre and Eaten Alive can be grouped together, although one was homegrown and filmed in Texas while the other brought Hooper to Hollywood. Both are totalizing visions, microcosmic conceptions of the world as echo chamber of suffering. Both were originally written or significantly reworked by the team of Hooper and Kim Henkel. They are loose and allegorical surveys of institutional American maladies treated onto slasher narratives, their expressive frenzy a mask for their deep lamentations. The director is sublimated by the rigor, the discipline, and the concerted purposes of the aesthetic expression. Chain Saw takes on American disillusionment and matters of class in an economy-based world; Eaten Alive retreats back to a more emotional, moralistic realm of Human Exploitation studies, locating cruelness as a spider’s web binary between rationality and primitiveness. It is a direct echo of Psycho, not only in their singular hotelier psychopaths: both martyr a woman of bravery only for men to die afterwards. Eaten Alive’s layering of several subplots suggest an interest in character-driven dramaturgy as much as film language; Hooper’s elegant, to-a-degree anonymous film grammar is in service first to story and the accomplishment of the moral telos of a piece, budging out matters of audience engagement and authorial fetishes. Finally, Eaten Alive presents Hooper’s first moral surrogate: the female character of “Libby,” marked by her chameleonic innocence and baseline kindness (one of the four final girls of the film). A lovelorn daughter of a stifling Southern patrician family, characterized by her blind trust and levelness based in ignorance of the exploiters surrounding her, Hooper identifies most completely with her – or at least in a tie with the film’s epigraphic martyr, who dies minutes into the film (the character of a troubled prostitute). The pronouncement of Hooper’s identification with these two female characters comes through the strength of the moral work – the two women are never denied or denigrated for their female experience (the rebellious daughter’s sex-working, the innocent daughter’s intimacy-starved life), but they embody sexless ideals (bravery, kindness). Eaten Alive never undermines such a moral undercurrent by never undermining a moral tenor and the unity of an aesthetic tenor. Such reliability is a trademark of Hooper, who never sells out a piece’s mature teleology, his unique sublimation making such a task immediately accessible.

His acclaimed TV miniseries Salem’s Lot, adapted from the Stephen King novel, served to show his stylistic range, finally being able to drop the raw, vérité “activity” of his previous two films and gifted with a dependable classical narrative to construct. Around this same time, Hooper was contracted under Universal Pictures where he (with Kim Henkel) wrote a passed-on treatment for the remake of The Thing From Another World, which was described, by The Thing remake’s producer Stuart Cohen (1), as an “Antarctica Moby Dick,” a “tone poem” with a “dense, humorless, almost impenetrable” script – also as “a disaster” (naturally). Hooper was said to have been uninterested in the original story’s tale of paranoia, wanting instead to “address the larger picture.” I believe John Carpenter is one of the true greats of cinema, but it is clear to me a Hooper film with guns and flamethrowers would cease to be a Tobe Hooper film.

His sole outing with Universal became The Funhouse, which remains a remarkable work, aiming towards the same totalizing allegories of Chain Saw and Eaten Alive but under the guise of the latest studio-prepared Friday the 13th knock-off. Showing a restraint and willingness to bind formula in a more freeform and associative framework, it is Hooper’s most formalistic exercise, characterized by spare and decisive frames. This is the Hooper film I most identify with that phrase of Godard (or Moullet) about the tracking shot invariably being “a moral choice.” Although Hooper is never one to have the camera flying and swooping in jigsaw puzzle editing of empty emphasis, The Funhouse is particularly a work of strategic stillness. Narratively structured in a way so as every scene is a new moral contemplation, it is only appropriate Hooper treat the scenes as such: flat, unembellished stages that appeal to our moral awareness. The materiality of Hooper’s mise en scène becomes the Pavlovian signal of a higher sensitivity he is asking from the viewer (also heightened by the beauty of it). Tracking is immoral cheapness – no wonder, then, it is saved for scrutiny of the film’s bad adult role models: a fake psychic; an intemperate magician with a wind-up-toy daughter, who mocks education with a history lesson to his audience about Dracula – née Vlad the Impaler – that he might have cared about at one point, but clearly does not anymore due to the anti-intellectualism of his youthful patrons (clear meta-textual implications included there).

Tracking is cheap, and so Hooper takes on Poltergeist, imitating and improving on Spielberg’s animated camera with a Mannerist sense: taking Spielberg’s punchy editing and unbalancing it with flat widescreen compositions, taking his visual jokes and padding them down with his shadows and irony, taking his romantic dolly shots and adding to them his off-balance spatial rhyme schemes. The surprising darkness and prickliness of Spielberg’s excellent script (if anything, Spielberg is attune to the emotional dynamics and the cultural politics of the relations of children with their Baby boomer parents, and is eager to push the personal hot buttons of defense mechanisms and identity crises gleaned from growing up in such an environment – see both Close Encounters and E.T. the Extraterrestrial) is fully served, if in an alternate way, by Hooper’s distanced, symbolic regard and ironical mise en scène. It is Spielberg’s brain, but Hooper’s removed but watchful style makes it feel texturally more like Nick Ray’s panoramic Bigger Than Life, if we are talking portraits of invaded American suburban life.

The prestigious production that was Poltergeist gave way to the more low-rent when Hooper transitioned to Cannon Pictures to make Lifeforce. An attempt at grand sci-fi filmmaking but more so a ruminative sexual odyssey film, it showed Hooper transitioning to a more appropriate protagonist/surrogate: a male trying to overcome the pangs of love and sex. Yet Hooper does not fixate on this stand-in so much as he creates a kaleidoscopic vision of love as universal madness, the honesty of our inner desperation as means of humanity’s rebirth.

Spontaneous Combustion is perhaps his greatest gesture, a project of very little commercial viability that plays out like a TV drama written for the screen, and that is meant as a compliment. Little to nothing happens in this film, other than the explication of nuclear history and the sacrificing of oneself for the power of love. There is no powerful mystery in this film, just the perfectly observed dramas and random displays of feelings.

Night Terrors (often distributed as Tobe Hooper’s Night Terrors) is his most adventurous film and, hand-in-hand, remarkably keen. Hooper fosters here a fair degree of analytical distance that makes the film a fascinating unfolding of real world textures taking place in far-off Israel (standing in for Egypt’s Alexandria), where the exotic is not the exotic but the rural, where we watch a provincial nanny perform a salt-pouring ritual on a windowsill with reverent ceremony, and where Hooper again identifies with a teenage girl and her inner life of moral awakening.

3. Hooper, the Aesthetician

I will jump to almost a decade later. One can see the lineage from the immensely underrated Eaten Alive to his 2004 slasher film comeback attempt Toolbox Murders, both made up of a series of minutest, but accumulating, moments devoted to an interlocking ensemble of characters. The unity of florid form throughout the respective pictures allows its early make-up of small gestures to erupt finally when the innocent heroes are suddenly and shockingly let into a world of cruelty and madness. Aside from Eaten Alive, Toolbox Murders mostly recalls Hooper’s Poltergeist, in which polished affects of genre are utilized consummately on more resolutely “popcorn” horror narratives. In both cases, Hooper pulls off some of his most unnerving work, rendering the interior spaces in both films as baroque and domineering as those of the mansion in Robert Wise’s The Haunting (‘63). But again, horror effects and a technical showcase are not enough for Hooper, who wishes to sublimate the easier achievements of genre for more lofty ones. This is why Toolbox Murders is a perfect throwback to classic Giallo occult-mystery tales (or, alternatively, Argento horror-fantasies), but makes no motions to truly capitalize on the kitsch value of such influences: Hooper’s valuing of reality prioritizes over “poetic” flourishes (as would be seen in Argento) what some may see as a mundane “literalism” with the story, which manifests in an acute sensitivity to situational matters over sensuous ones. For his craft is just too tied with a preeminent humanistic concern, which is then tied back to cinematic concern. Toolbox Murders thus ceases to be a Giallo throwback and becomes an incisive situational comedy – Fawlty Towers but concerned with a Hollywood-fashion slumlord locking his tenants into residency with a murderous wraith, while a radical heroine-tenant tries to dismantle the establishment from within. Toolbox Murders is no great transcendent shakes, but it becomes a pleasure when viewed as an artful sitcom about the communal stresses of coerced urban living conditions. That is, before it dips into its hellish finale – following a tradition carried out through Texas Chain Saw, Poltergeist, and The Mangler (1995) – which strikingly realizes Hooper’s metaphorical fervor, depicting its heroine fighting for her life within a limbo space created by two Hollywood ghosts, one representing vanity and the infantile mindset while the other the graceful slide into age and finally to a natural, parental death; other films may have the gravity and topicality, but Toolbox Murders has the giddy whimsy of Hooper’s genre-indebted sense of discovery.

"All that is poetic in character should be rythmically [sic] treated! … [If] even a sort of poetic prose should be gradually introduced, it would only show that the distinction between prose and poetry had been completely lost sight of." – Goethe to Schiller, 1797

“Poetry is not simply a fashion of expression: it is the form of expression absolutely required by a certain class of ideas.” – Bayard Taylor, Preface to his translation of Goethe’s Faust (in the original metres), 1872

4. Hooper, Neither Goethe’s Poet Nor Merry-Andrew

Though poetic filmmakers do exist, we (filmgoers) are by nature not in the realm of poetry. So Goethe would have insisted, so as to keep the form of poetry pure. In this new art form of film, the indexical image somehow is asked to substitute as poetry, or art. The old ideal – which was to form the image out of nothing, out of complete abstraction – is now marginalized by what storytellers can do with the photographic record. Thus, theorists, artists, philosophers, and, of course, critics have had to rethink just how this new medium reconciles the conception of the ideal immaterial (of Beauty, Truth, and Goodness conjured out of thin air, by the mind, then relayed to the brush, to the pen, etc.) with the new language of film and, perhaps, constructed narrative. Somehow we have formulated the idea that the empirical record caught on photo film (or digital) and manipulated can indeed be Art, and is simply a new system for uncovering Truth that is immaterial. But this need not be achieved solely by a fleeing to the realms of pure expressionism, poetic or otherwise (let us mercifully ignore the idea of the fifty-to-one-hundred-percent Computer Generated Image for now). Goethe insists on the categorization; he dwelt obsessively on the matter as a poet working alongside the philosophical writing of Weimar Classicism, the Enlightenment-era movement from which I have derived most my conceits. Poetry is a realm of emotion and ideals he claims even prose cannot attempt, so one imagines far be it for film – though filmmakers the likes of David Lynch and Jean Cocteau fight for the right to film poetry. But I bring up Goethe – dramatic poet, aesthetic worrywart, and great friend of Schiller (preeminent philosopher of Weimar Classicism) – only to make the point that Hooper is not Goethe’s poet in the realm of film. What is Hooper’s form of expression? And so, what is his “class of ideas” that is not poetry’s total conception of “form as substance,” nor prose’s more novelistic “substance as form”? Through the indexical, we can still retreat, not to poetry or games of manipulation, but to philosophy (or to that very first conception of art, which was as Rhetoric), where substance and form are less relational but truly one, caught in a dialectic and reflexive feedback loop of rationality posed in relation to beauty, morality as, without question, caught up in aesthetics – with the by-product, naturally, being the Good. Hooper is both the indexical (Hooper the documentarian, committed to the world) and the absolute (Hooper the aesthetic philosopher, who believes cinema can approach Truth). Neither the full-blown populist nor the sensuous fine artist caught up in his own mind, Hooper’s art is one that philosophizes itself.

Griffith is of the theatric model, Murnau is the poet (perchance by way of Goethe), Eisenstein dances while Rossellini paints, and Renoir makes music – so Jean-Luc Godard’s well-known distribution goes. By deduction, Hooper is the philosopher (along with the likes of Nick Ray). Hooper and Ray less engage their own fancies as they engage the real world in a rhetorical way, apart from themselves, while striving for ideals in the philosophic tradition. They question and dive into each new film like wide-eyed Socrates, often finding new ruminations separate from their other films.

The lyric from the songwriter Joanna Newsom I began this article with continues on with a chanted disavowal of the body: “Let each note be a full-bodied song / Enough fingers, enough toes! / Skin to cover the bloody beat / Enough belly, enough feet.” As opposed to art too much of the self (and the overly appendaged), these artists promote full-bodied visions with each film. If one watches closer, it can be said they do so with each scene, with each shot they choose, which are chosen to best represent the world. The self, the body, and the artist sublimated, their work thus speaks for itself.

| Tweet |

|

|

|